G.A. Benton, writing for Columbus Alive, just released a very thoughtful and kind homage to our founder and my old man. Here it is on our site, please use Columbus Alive's link as credit for the article and pictures.

You can hardly toss a bottle cap these days without hitting a new, hops-happy Columbus brewery. But to think of our town as an emerging hotbed of IPAs is like celebrating the Kinks without knowing about the Rolling Stones and the Beatles.

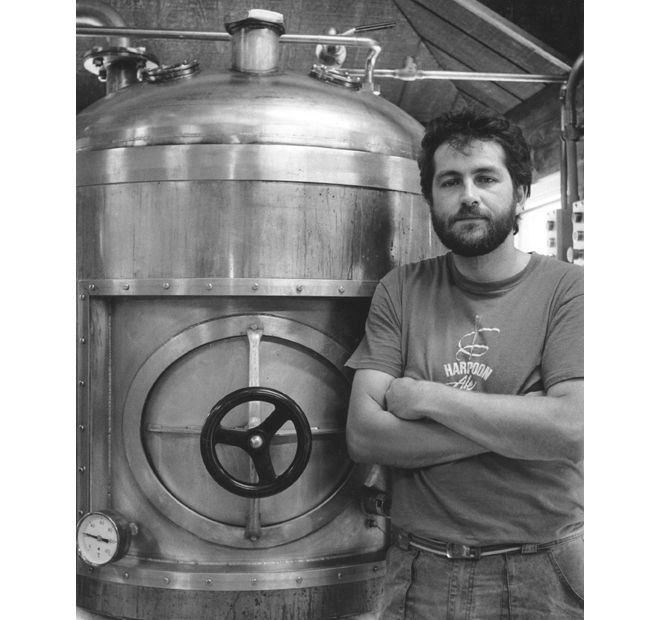

Just as every flood starts with a trickle, the currently gushing Columbus beer movement had a humble start with an under-acknowledged founding father. His name is Scott Francis — that Kinks analogy is his, by the way — and this is his story.

“I was in the right place at the right time, but I was obsessed” is how Francis explained he came to brew the first batch of what is now called craft beer in modern-day Columbus (some context: the previous last, independently owned Columbus brewery, August Wagner, went belly up back in 1974). Francis was lounging with his bare feet atop a coffee table in the living room of his handsome Clintonville house. The table faced a comfortable porch overlooking a manicured, garden-like front yard. This was the pleasant setting for two relaxed, late-afternoon conversations in which, with disarming candor and humor, Francis recounted his long and pioneering career as a local brewmaster.

The “right time” Francis was referencing is the late 1980s — the last years of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. The place was the Brewery District, a history-rich but then-sketchy patch of Columbus slowly awakening after decades of dormancy.

This is how Angelo Signorino, head suds-honcho at Barley’s Brewing Company and Francis’ star pupil, sums up what happened then: “[In 1988] Scott started the original Columbus Brewing Company to make authentic British-style ales at a time when nobody knew what ‘microbrew’ was, let alone wanted to drink it.”

Francis, who produces stellar beers at Temperance Row Brewing in Westerville these days — smooth and creamy “nitro” ales are emphasized there — would go on to launch the beer operations at numerous other breweries, including Barley’s and what used to be called Barley’s Smokehouse and Brewpub. In the process, Francis would inspire and influence countless local brewers.

“I’ve known Scott for about 17 years, and he’s always been the go-to guy in town — has always been helpful and insightful,” said Eric Bean, current brewmaster-slash-owner of Columbus Brewing Company, the business that Francis started with outside funding nearly three decade ago.

“He’s like Obi-Wan with a pint glass instead of a light saber,” said Colin Vent of Seventh Son, Alive’s recently selected 2016 Brewer of the Year.

Because of the work this local-ale visionary did during a time of corporate-lager complacency, you could say that every sip you take of great local beer has a bit of Scott Francis in it.

Voted Most Likely to Get the Last Laugh

Long before obsessing about draft beer, the draft that got Francis’ attention was the one for the Vietnam War. That interest landed him in the pages of Time magazine at the tender age of 18, when Francis became “the youngest person ever elected to public office in the country at the time.”

The time was 1971. And 18-year-olds such as Francis had just won the right to vote — previously, you had to be 21 — due largely to their mandatory inclusion in the draft. The office Francis was elected to was a seat on the Reynoldsburg school board. This was especially sweet because Francis, who said, “I was more into politics than academics,” began overseeing the actions of the same teachers and antagonistic school system that had suspended him for “insubordination.”

However, it was not politics, but a seemingly insignificant gift his mother bought him a couple years prior to this shining political moment that would shape the rest of his life. She bought him a winemaking kit.

Vintage Columbus

How was the wine Francis made back then? “It was good only in the sense that it was alcohol,” he said. But it led to a life-changing decision: In 1974, with help from his brother, Francis purchased the Winemaker’s Shop in Clintonville, a business he still owns.

There, he would meet his future wife and Winemaking Shop partner, Nina Hawranick; their 38 years together began when she applied for a job. After homebrewing became legal — which happened in 1978 — the refocused shop would eventually become an incubator for innumerable Columbus brewers and a veritable temple of beer-making knowledge. Lean times were common in those early days, but sporadic business meant more free time to dabble in homebrewing and to read everything possible on the subject.

Moving into the mid-1980s brought an evolving cultural awareness of beer accompanied by an increasingly cosmopolitan Columbus market and an influx of previously rare, imported brews (Francis’ face went dreamy as he recalled his first sip of Samuel Smith’s pale ale). This helped trigger developments such as a growing interest in domestic beers deviating from the common American style, access to vastly improved homebrewing supplies (Francis described how a sympathetic West Coast distributor of high-grade hops would also ship him prized bottles of impossible-to-get-in-Ohio beers hidden in the hops bales) and to Francis making his first batch of all-grain ale. Upon tasting how good his homemade beer could really be, Francis knew he was on to something. But the next step would be a doozy.

Home is Where the Art is Learned

Like a talented athlete who has accrued enough experience that a fast-paced game seems to slow down, Francis’ confidence and ambition began to catch up with his ever-improving homebrewing abilities. But, while most brewmasters begin as accomplished homebrewers, the jump into the professional arena isn’t unlike a weekend warrior who scores a few touchdowns playing with his buddies transitioning into an NFL quarterback suddenly facing a fearsome defense. Besides, the first and only microbrewery in Ohio had just premiered (Great Lakes, Cleveland, 1988), so who was going to finance him to open another microbrewery, something few people had heard of or cared about?

Complicating matters was a brutally scorching summer that had seen Francis’ homebrewing business drastically dwindle, as brewing involves big pots of boiling, thick liquid and hot, hard work. Then came news that he and Nina were going to have a baby. With the shop open only a couple days a week, Francis began working construction jobs to help make ends meet.

Hope flashed when he learned about the Brewery District redevelopment plans. Connecting a few dots, he reached out to one of the movers and shakers and made a proposition: If the developer would pay for this newfangled thing people were calling a microbrewery, Francis would be its brewmaster. When the answer was “no” Francis said, “My dream was falling apart in my face.”

But just as a bubbling hot, heaving pot of sweet wort can produce a deliciously bitter, chilled bottle of beer, on a particularly terrible day when Francis said, “I was at the end of my rope,” he got a call from that developer — it was Jeff Edwards. Edwards had reconsidered, and would take Francis up on his offer after all.

“I Knew I Didn’t Know What I Was Doing”

To produce a good batch of beer from scratch, a lot of elements need to harmoniously come together. To produce a brewery from scratch requires a similar synergy, but on a massively grander scale. But to produce a brewery from scratch when you’ve never even worked in one requires synergy, gumption, hubris and, if you’re smart like Francis — yes, that quote above is his — help from people who’d already been through it and knew what the hell they were doing.

Things started to move fast. In relatively short order, Francis recruited professionals with brewery experience in New York, Boston and Oregon to help him select, ship and erect in Columbus equipment purchased in England. He earned a degree from the Siebel Institute of Brewing in Chicago. And, in an important move Francis duly believes too-few new brewers choose — and so they instead learn on the job by initially making some not-so-good beers — Francis paid $1,000 out of his own pocket (and that was 1989 dollars) to apprentice under an established brewmaster whose name will come up again: Victor Ecimovich of then-fledgling Goose Island in Chicago.

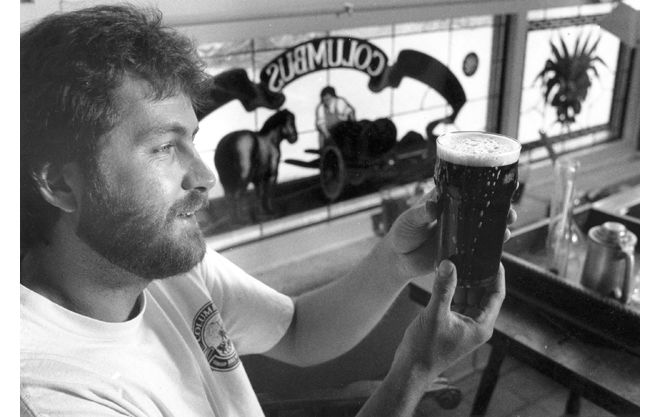

Result: The first professional batch of craft beer brewed in Central Ohio was a pale ale Scott Francis produced under the aegis of Columbus Brewing Company. And it rocked.

Band of Brewers

Francis busted his hump, but CBC wasn’t an instant success — Signorino remembers Francis saying that, in those days, "It was easier to make good beer than it was to sell good beer." Eventually, though, that delicious pale ale would catch on and become the spark that would ignite a fire.

About a year after CBC opened, the first Columbus brewpub premiered. It was called Hoster’s, and Victor Ecimovich was its talented brewmaster. “They were the kings of the hill then,” recalled Francis.

Francis, a part-time musician, managed to snag a few outside accounts by selling kegs to the legendary Stache’s music club. One of the bartenders Francis dealt with would become his brewing disciple and hand-picked successor as CBC brewmaster: Ben Pridgeon, who played in prominent local bands such as RC Mob and the Squids.

By the time Francis effectively left CBC to launch the beer arm of Barley’s in the early ‘90s, more consumers were familiar with — and actually seeking — beers outside the box of light American lager. Barley’s was an instant success, or as Francis put it, “insane off the bat.” The Grandview-area Barley’s would follow about five years later; it’s now called Smokehouse Brewing Company.

As the budding movement unfurled through osmosis, camaraderie and generations, The Winemaker's Shop was a lingering hub of activity. Signorino said he went there as an amateur in 1991 “on a pilgrimage for homebrewing advice.” Vent agreed that, “To get started, you went to The Winemaker's Shop,” which Vent began frequenting in 2005 while a chef at DeepWood.

The annual homebrewer’s contest held at Barley’s became another breeding ground for the craft beer movement. There, Francis and his coterie of brewing-professional judges would swap stories, hang out and meet nascent brewers destined to spread the gospel. Contest winners went on to found places such as Weasel Boy Brewing Co. in Zanesville and Pigskin Brewing Company in Gahanna. The local beer scene was buzzing, and Scott Francis was in a very nice place.

Out of Beer

Tweaking a cliché, though, ironic shit happens. Due to business relationships that terminated, sometimes on a sour note — and the kind of dramatically timed narrative twists common in corny movies — right when an orchard of local breweries began to bloom, the man who planted the first craft-beer seed in Columbus was without a brewing job in the city. It was 2010 and, pushing 60 and with adult children, Francis confessed, “I got to the point where I wasn’t sure I ever wanted to brew again.” Besides, he said, “No one called me.”

Finally, someone called. Looking to get in on the burgeoning local craft beer action, the Jimmy V’s restaurant team had been hanging out at North High Brewing where, from recipe creation to bottling, pros will walk novices through every step necessary to produce a batch of beer. As one thing led to another and the North High folks realized that the Jimmy V’s people were serious about opening a brewery, the North High guys advised them to get ahold of Scott Francis. It was, as they say, the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

What’s on Tap

In 2014, Francis inaugurated beer-making operations at Temperance Row Brewing in Westerville — yes, the former “Dry Capital of the World” — to become the “Brew” part of Jimmy V’s Uptown Deli and Brew. Not only does Francis get to make beer with his son there, but he says he’s “treated like a king.” He loves focusing again on his beloved British classics — Francis compared the ever-bigger-and-hoppier beer craze to a fad, à la trying to outmuscle your competitors with ever-spicier chicken wings — and he’s convinced that more-balanced pale ales will become prominent again.

Francis also enjoys creating seasonal brews such as the watermelon wheat beer that’s currently all the rage at Temperance. And, at Temperance, he even recently got to collaborate with his old colleague Victor Ecimovich to revive a spectacular Columbus classic: Hoster’s Gold Top, which hadn’t been available in more than a decade.

Might there be another brewery in his future? Although the days of Francis running five breweries simultaneously are long gone, he told me he’s got all of the necessary equipment for another brewery in storage, and that sometimes he daydreams about a little place that would only be open on weekends and would only offer three taps and maybe some peanuts and cheese and crackers.

Will that actually happen? Maybe — but it’ll take another call.